home // store // text

files

// multimedia // discography // a

to zed

// random

// links

home // store // text

files

// multimedia // discography // a

to zed

// random

// links

Long after even the most celebrated

guitarists of this age have been forgotten, their picking hands

turned to putrid dust, Nigel Tufnel will be hailed for his manifold

contributions to rock and roll. Tufnel's brilliant two-decade

plus stint as lead guitarist with England's now-legendary Spinal

Tap has earned him an eternal place in the pantheon of rock guitar

legends. His pioneering use of such techniques as "hair

popping," his virtuosic facial contortions, and his gut-wrenching

solos on anthems like (Tonight I'm Gonna) Rock You Tonight have

delighted millions and caused thousands of guitarists to set

themselves ablaze. Long after even the most celebrated

guitarists of this age have been forgotten, their picking hands

turned to putrid dust, Nigel Tufnel will be hailed for his manifold

contributions to rock and roll. Tufnel's brilliant two-decade

plus stint as lead guitarist with England's now-legendary Spinal

Tap has earned him an eternal place in the pantheon of rock guitar

legends. His pioneering use of such techniques as "hair

popping," his virtuosic facial contortions, and his gut-wrenching

solos on anthems like (Tonight I'm Gonna) Rock You Tonight have

delighted millions and caused thousands of guitarists to set

themselves ablaze.

Nigel was in rare form during

our all-too-brief conversation, from which the following exclusive,

private lesson was culled. Composed, candid and virtually overflowing

with phlegm and keen insight, the personable guitarist demonstrated

why, as repulsive pretenders come and go, he and Spinal Tap remain

magnificent, if malodorous, fixtures in the world of hard rock. Nigel was in rare form during

our all-too-brief conversation, from which the following exclusive,

private lesson was culled. Composed, candid and virtually overflowing

with phlegm and keen insight, the personable guitarist demonstrated

why, as repulsive pretenders come and go, he and Spinal Tap remain

magnificent, if malodorous, fixtures in the world of hard rock.

GUITAR WORLD: There are reports

that you've devised a Nigel Tufnel Theory of Music. What exactly

is this theory?

NIGEL TUFNEL: This is an exclusive

— it's not been published before. Here's the theory: People

read music, and they read notes on what they call a staff. But

if you can't read music, you can't play music that is written.

Correct? You're with me on that? Good. Now, everyone knows how

to count, don't they? Let me hear you count to five.

GW: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

TUFNEL: Good. Now, A is the first

letter of the alphabet. Yes? So A would be...?

GW: 1?

TUFNEL: Yes! So on a chart, instead of

writing A in music terms-we're playing in the key of A-you go:

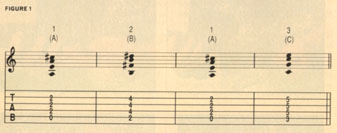

I for A, 2 for B, 1 for A and 3 for C. See? [Fig. 1] That's

so much simpler. TUFNEL: Yes! So on a chart, instead of

writing A in music terms-we're playing in the key of A-you go:

I for A, 2 for B, 1 for A and 3 for C. See? [Fig. 1] That's

so much simpler.

GW: What happens in the case of

a chord like G13?

TUFNEL: Okay. This is my other

theory:

If you're playing that type of music, you shouldn't be doing

it.

GW: Shouldn't be doing the Nigel

Tufnel Theory of Music?

TUFNEL: No — you shouldn't

be playing

music! Because what good are people who do that jazzy sort of

stuff? It's all too low-volume. Have you noticed that? What are

they trying to hide? What have they got to be embarrassed about?

If you're a good player, you play loud so people can hear it-that's

why we plug these things in. If you play an electric guitar —

I don't care if it's a Gibson 175 or a Charlie Christian —

turn the fuckin' thing up!

To those people who do that

13th stuff I say, "By the time you count to 13, who cares?

The song's over anyway. So let's play some serious rock and roll."

It's all very impressive, I suppose, for some musicologists who

play jazz and all that — let them have their way. But they

must be afraid of something if they're not playing loud. To those people who do that

13th stuff I say, "By the time you count to 13, who cares?

The song's over anyway. So let's play some serious rock and roll."

It's all very impressive, I suppose, for some musicologists who

play jazz and all that — let them have their way. But they

must be afraid of something if they're not playing loud.

GW: Getting back to the Nigel Tufnel

Theory of Music: where does a B flat fit in?

TUFNEL: I've invented a little

symbol to deal with that. You know how it is in music notation-the

flat one looks like a little B [b] and the sharp one looks like

crosses with a little square in the middle [#]. Well, my system

replaces those with different-sized circles. The basis for this

is Stonehenge, which is designed around a circular theme. You'd

know this if you were ever in a helicopter or plane looking down

on Stonehenge. You haven't? [Shakes head with contemptuous

wonderment.] Let me show you how this all relates on a piece

of  paper:

Here's my music chart [Fig. 2]. We'll make it a trite,

pornographic ditty and call it Wolf's Song. Now, the chords would

be A-A-B-A-Ab. paper:

Here's my music chart [Fig. 2]. We'll make it a trite,

pornographic ditty and call it Wolf's Song. Now, the chords would

be A-A-B-A-Ab.

GW: What if it was A#?

TUFNEL: Aha! Put the circle up

here [Fig. 3]. It's easy to read-flats are lower and sharps

are higher. Now, the other thing I'm doing is taking unpleasant

folk songs and turning them into things that people can appreciate.

For instance, if an exhausted thing like Skip To My Lou is done

loudly  enough, it's no longer the strict property

of social workers specializing in geriatric care. Because old

folks will say, "Oh Cor, turn it down! It's too fuckin'

loud!" I say, play it loud and it's for everyone —

except the old folks. enough, it's no longer the strict property

of social workers specializing in geriatric care. Because old

folks will say, "Oh Cor, turn it down! It's too fuckin'

loud!" I say, play it loud and it's for everyone —

except the old folks.

GW: What new technical tricks have

you got up your greasy sleeve these days?

TUFNEL: On the new record, I do

some scatting while I play guitar. It's live — I don't know

any other way of doing it — and I don't use a talk tube

like the old boys do. It's hard to describe the maneuver, but

let's

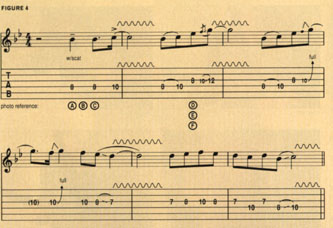

say you're playing in C [plays Fig. 4]. People think,

"What's that noise? Who's doing that?" But it's an

illusion — an aural illusion, a sort of parlor trick. It's

my voice, you see. It's really just my voice with the guitar. let's

say you're playing in C [plays Fig. 4]. People think,

"What's that noise? Who's doing that?" But it's an

illusion — an aural illusion, a sort of parlor trick. It's

my voice, you see. It's really just my voice with the guitar.

GW: Do you practice this technique?

TUFNEL: No, there's nothing to practice

— it's all improv. You can't practice it; you just wake

up and do it.

GW: What about intonation and rhythmic

synchronization?

TUFNEL: Well, I suppose you could practice

it, but I don't. It just developed naturally — sort of like

a rash. If you wake up in the morning and you feel, "Oh

hell, this is itching!" You lower your trousers, you look

down and you say, "Oh hell, it's a rash, isn't it?!"

You don't practice a rash, you just let it evolve and grow and

spread. This is really very much like that.

GW: Could you demonstrate the most important

elements of the idea?

TUFNEL: Sure. First, we'll show hand,

then mouth, then both together. For example, this would be the

first note [Photo A] and this would be my mouth's first

note [Photo B]. Together they are.. .[Photo C].

See? This is the hand and mouth position for the third note [Photos

D and E]. Next, the combination [Photo F]. The tough

one, of course, is the high E. The kids probably shouldn't try

to do this one without some sort of warmup. I recommend a bowl

of hot porridge or a tankard of steaming Ovaltine.

GW: How do you incorporate harmonics

into your playing?

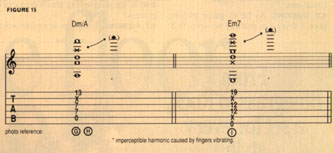

TUFNEL: I'll demonstrate: Begin by barring

across here [Fig. 5 and Photo G]. What you've got

is sort of a minor chord [note: D minor — the tonic chord

in "the saddest of all keys]. There are easier ways

of playing this, no doubt, but that's not the point. The point

is that these [2nd and 3rd fingers: see Photo H] set up

a sympathetic vibration.

GW: That's very subtle. The fingers

actually vibrate?

TUFNEL: [Nods, smiles condescendingly]

The fingers vibrate. Where do you think the sound goes? It

doesn't go into a hole and disappear and shout, "Help me,

doctor, I'm alone." It emanates from the guitar. So, it

goes out here [from the chord] and there's an imperceptible

vibration between these two fingers [2nd and 3rd] as it

happens. The lower you go down the neck, the more slowly they

vibrate. As you go higher [Photo I], they vibrate quite

rapidly. And funnily enough, it's an overtone — always an

overtone. TUFNEL: [Nods, smiles condescendingly]

The fingers vibrate. Where do you think the sound goes? It

doesn't go into a hole and disappear and shout, "Help me,

doctor, I'm alone." It emanates from the guitar. So, it

goes out here [from the chord] and there's an imperceptible

vibration between these two fingers [2nd and 3rd] as it

happens. The lower you go down the neck, the more slowly they

vibrate. As you go higher [Photo I], they vibrate quite

rapidly. And funnily enough, it's an overtone — always an

overtone.

GW: Any other new developments

on the fingerboard front?

TUFNEL: I've got another wonderful

trick I do. Let me draw your attention to the screws on the pickup.

[Photo J]. You'll notice that these are Phillips screws,

but the middle one [Photo K] is a regular screw —

a straight screw. Most people have two straight screws made of

titanium and a Phillips made of magnesium. Now, if you flip them

— as I do — there's a whole different interaction between

the pickups, even with single-coils. But these humbucker pickups

in particular reverberate in a very different way. It's all about

reverberation — that's what all this is about. They must

be switched for reverberation. That's for people who are into

rewiring their guitars.

GW: Do you modify your guitar in

any other way?

TUFNEL: Here's another thing. Most

people think that once you're off the frets, you go, "Lordy!

I can't go any further than the F!" Wrong. Of course you

can go further than the F — if you want it bad enough. And

I do, sometimes. But as you go diving down to the nut, it's very

easy to hurt your finger. As you can see, I've got festering

wounds — see the pus? — here from diving onto the nut

one too many times. So I've designed a great, patent-pending

device — which has yet to be installed on this guitar —

called a Nut Cozy. It's a little knit thing, made of wool, that

fits over the nut. I've also designed a Tone Cozy, a similar

thing that fits over a control knob. It droops a little bit.

Next, of course, will be a Volume Cozy. I've got a little cottage

industry going, producing them, and readers will be able to send

away for  them

soon. My Nut Cozy is great, because if you bash your finger down

here [Photo L] it's soft. them

soon. My Nut Cozy is great, because if you bash your finger down

here [Photo L] it's soft.

GW: Have you ever discovered any

valuable techniques by pure chance?

TUFNEL: Sure. A lot of the younger

kids tend to play their guitars hung way down on their knees.

They play real low because they think it looks sexy or something

— God knows what they're doing. Anyway, that sort of thing

is impractical for the older player, or the old at heart; there's

too much weight on your back. So what I do is, I use a short

strap and have the guitar sitting higher. Now this was the accident:

One  night

I was playing up here [Photo M], and my hair, by mistake,

got on the strings [Photo N]. And what I discovered, by

accident, is that this contact triggered an organic overtone.

You see, if something like metal touches the string, it's not

organic. But if it's part of your body, it's totally organic,

and it sets off a very beautiful resonance. All the great players

are aware of these things. night

I was playing up here [Photo M], and my hair, by mistake,

got on the strings [Photo N]. And what I discovered, by

accident, is that this contact triggered an organic overtone.

You see, if something like metal touches the string, it's not

organic. But if it's part of your body, it's totally organic,

and it sets off a very beautiful resonance. All the great players

are aware of these things.

GW: Does "hair touching"

actually produce a distinctive tone?

TUFNEL: Yeah. You'll hear a lot

of hair popping in my solo on Christmas With The Devil. You'll

also hear a lick in that solo based on chromatism [chromaticism].

It's beyond anything musical. If you play a scale, it's just

a scale — it doesn't link people together. Chromatism does

— because it's  from chromosomes! from chromosomes!

GW: What is your view of the of

the guitar's role in music?

TUFNEL: Well, every instrument

has its own personality. For example, I love the piano for the

depth of its feeling. But the piano is not really an instrument

— it's really taking an orchestra, shrinking the people

and putting them in a box. The guitar is actually an opera singer

with a long neck. If you're not making it sing, you might as

well go home.

GW: I'm going home.

|